Kenya Year Launched International Interest

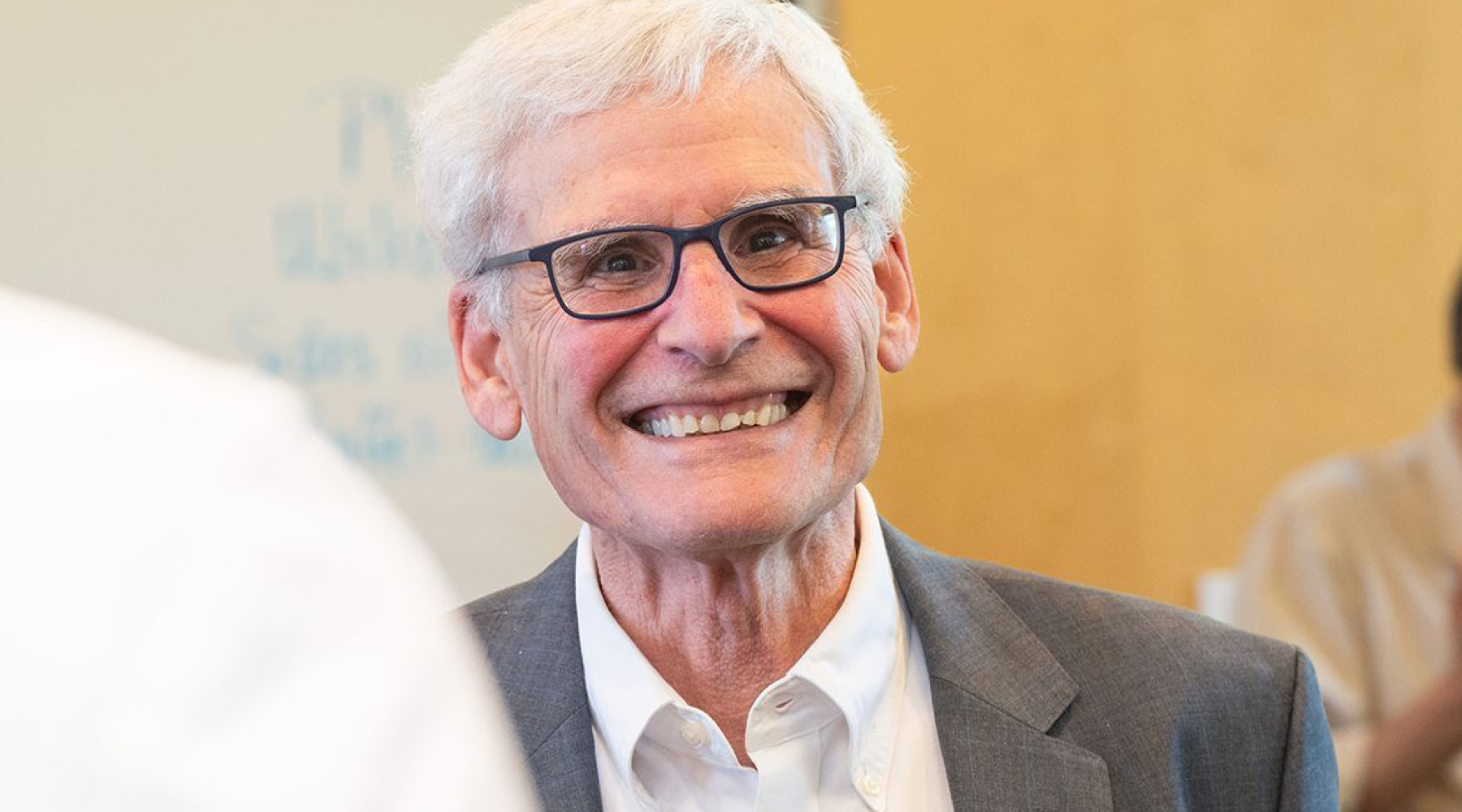

After 50 years of teaching in the Ivy League, Gary Fields retired this year as the John P. Windmuller Professor of International and Comparative Labor. His work has taken him to many countries, earned him the acclaimed IZA Prize and stretches to 14 pages on his CV. Recently, Fields discussed how he found his way to labor economics and how his career unfolded.

What motivated you to study labor economics?

I was a not-yet-18-year-old freshman at the University of Michigan when I started taking social science courses. (My high school did not offer any.) Of the various ones I took, economics spoke the most to me, because it was the most mathematical, and therefore the most rigorous, of the social sciences. Within economics, labor economics was the field I found most meaningful for dealing with people problems. What is remarkable that I took my first labor economics course in 1966, and I am still enthusiastic about labor economics today!

What led to you becoming a professor?

A life-changing conversation with a professor, George Johnson. In my first undergraduate labor economics course, George gave us eight study questions for the final exam, of which four would be asked on the exam. Dutifully, I studied them all. The actual exam had four questions, three of which were identical to what was on the study guide, but one was different. When I went in to pick up my bluebook, which I always did, I asked George why he had changed Question 4. He asked me what I meant. I told him how I found the question he asked to be different from the one on the study guide. He then asked me how I would have answered the question on the study guide, and I told him. “A good answer,” he said, and I then left.

Two days later, I received a letter in the mail (email did not yet exist) saying that my grade in the course had been changed from B to A. When I went in to thank George, he told me that he thought he had merely changed the wording of the question, but after hearing my answer, he realized that the meaning of the question had changed and that I had given an excellent answer to the question he had intended to ask. Then he asked me what I was planning to do when I graduated. I answered that I was planning to get an MBA and then go to law school. George said, “You’re very good at economics. Why don’t you become an economist?” And he continued, “I’m on the admissions committee. We are meeting tomorrow. If you fill out an application before we meet, I will make sure the committee considers it.” I did, they did, and so I became a graduate student in labor economics. Of course, George became my Ph.D. adviser. All this at the “big, impersonal” University of Michigan! More of the Michigan story to follow.

Was teaching a passion that developed when you were a teaching assistant? Or perhaps it was a love of research that inspired you to go into academia?

I became a TA in my second year of grad school. I found I really liked it and was very good at it. And so, I decided that I wanted to become a professor.

As for love of research, when I got to the dissertation stage, I had a couple of false starts, as do most other grad students. The best thing that happened to me early in my “dissertating” was that I gathered original data, ran my regressions and found that none of the explanatory variables came out statistically significant. Nobody had to advise me to choose a new topic under the circumstances. I started to research the new topic, but then George Johnson intervened in another life-changing way.

Tell me about it.

One night, the phone rang in our apartment. My wife, Vivian, answered the call. All I could make out from what I heard at our end was Vivian telling George, “I will work on Gary.” George had told her that as part of a Rockefeller Foundation grant that was taking George to Africa for a year – specifically, to Nairobi, Kenya – money was also available for a graduate student to go along too. Did we want to do it? In about 10 minutes, Vivian convinced me that we should go. She realized the importance of being open to new life experiences and not trying to rush ahead as quickly as possible. And that is how I came to be an internationalist.

What was it like to be an internationally-oriented labor economist?

Much to my surprise, I found that field to be wide open. I had thought, naively as it turned out, that the study of economic development would be guided by labor economists for the simple reason that in situations of mass poverty, most people receive most, if not all, of their income from the work they do (including both wage-employment and self-employment). But I did not see trained labor economists writing about these issues. This was a great opportunity for me to take the labor economics I had learned and apply it, with appropriate modifications, to the study of developing countries.

I started on a new dissertation, looking at the interrelationships between education and labor markets in Kenya and other economies of that type. George Johnson was my committee chairman for my first dissertation year and Frank Stafford for my second. They were excellent advisers in every respect. Knowing how much they helped me is what led me to be a conscientious Ph.D. adviser once I graduated and took up a faculty position.

After a while, George and Frank told me that they thought I was writing two dissertations at the same time – one theoretical and one empirical – and urged me to choose one. What I chose was empirically-based theory. I did this because of two eye-opening papers I encountered in the library of the Institute for Development Studies at the University of Nairobi. One was John Harris and Michael Todaro’s “Migration, Unemployment, and Development: A Two-Sector Analysis,” American Economic Review, March, 1970: 126-142. The American Economic Review is one of the top economics journals in the world. Later, the Harris-Todaro paper would be named one of the top 20 papers published in the AER’s first hundred years of existence. The other pivotal paper in my thinking was a working paper by a young economist only a few years older than I, Joseph Stiglitz, who was already a tenured full professor at Yale at age 26. Stiglitz’s working paper laid out models of efficiency wages, which were only then coming to be formalized, mostly by economic theorists as opposed to labor economists.

Following the theoretical course proved to be a felicitous choice. Stiglitz appeared in Nairobi near the end of my year there. When we met, the conversation started predictably. Stiglitz: “What are you working on these days?” I told him about my model. Stiglitz: “Thanks, but I like to do my own thinking.” I: “I’m sure you do.” I continued my dissertation work.

The next year, when I was on the job market, Yale approached me about a job teaching labor economics in the Economics Department and doing research at the Economic Growth Center. It looked like a job perfectly designed for me, and so I accepted the offer. Later, I learned that the job description had been designed for me.

The year after that proved to be my first year on the Yale faculty and Stiglitz’s last. Stiglitz and I enjoyed many truly memorable conversations about labor market models over delicious New Haven pizza.

Fast forward to 2001, when Stiglitz won the Nobel Prize in Economics. Imagine my surprise and delight when I heard my work described approvingly in his Nobel acceptance speech!

Why did this happen? The luck to be invited to go to Kenya. Vivian’s wisdom in urging us to accept it. The luck to meet a future Nobel Prize winner. And the fact that when asked about my research, my work was developed far enough that my answer impressed him.

How did your career unfold after that?

After four years at Yale, I was promoted to non-tenured associate professor. A year later, at two different conferences, I met two full professors at ILR, Ron Ehrenberg and Walter Galenson. Both asked if I was movable and whether I would be interested in a position at Cornell. Yes, I said, if it involved immediate tenure. The fact that they could agree on hiring me (I learned later that they didn’t agree on much) led to a tenured offer, which Vivian and I accepted. ILR and the Department of Economics offered me the right mix of teaching, research and policy work in the areas of labor economics and development economics, and Ithaca offered a beautiful living environment, a fine community and excellent public schools.

We never dreamed that we would stay anyplace for 46 years. Despite outside offers, we stayed, because this was the best place for us to be.

Tell me about the importance of research, teaching and policy work to you.

The beauty of my career has been the interplay between the three of them, both within Cornell and outside. What I researched is what I taught, and what I taught is what I did research on. And policy work is highly valued here.

I had two career-long research streams - labor markets in developing economies and income distribution – along with some other issues that came and went.

The work on labor markets in developing economies aimed to understand how developing country labor markets operate and what might be done to improve labor market conditions for workers in low- and middle-income countries. The most accessible of my books for laypersons is Working Hard, Working Poor (Oxford University Press, 2012). Some of my most important writings for professional audiences are collected into my IZA Prize volume (Employment and Development, Oxford University Press, 2019). My latest (and last) book (The Job Ladder: Transforming Informal Work and Livelihoods in Developing Countries, co-edited with T.H. Gindling, Kunal Sen, Michael Danquah and Simone Schotte, Oxford University Press, 2023) is attracting attention in research and policy circles today.

The other main stream of my research is income distribution, which includes the topics of poverty, inequality, income mobility and economic well-being. My two most important works on these topics are Poverty, Inequality, and Development (Cambridge University Press, 1980) and Distribution and Development (MIT Press and the Russell Sage Foundation, 2001).

Turning to teaching, throughout my years at Cornell, I taught three courses: introductory labor economics, Ph.D. development economics and an advanced undergraduate/professional master’s elective on labor markets and income distribution in developing economies.

As you can see, my teaching, research and policy work feed off of one another. This is what made being a professor at an Ivy League research university so special.

What impact did your work have?

Let me share two fundamental insights with you.

On the topic of labor markets, the principal labor market problem in the developing world is not unemployment (defined, following the standard international definition, as workers actively looking for jobs but not doing any work at all). Rather, the problem was (and still is) an insufficiency of well-paying jobs. This is because developing country labor markets are segmented, meaning that there are not enough good jobs for all who want them and are capable of performing them. On the policy side, although employing the unemployed is important, far more important numerically is improving earning opportunities for those who are now working but earning little for the work they do – hence, Working Hard, Working Poor. The international Conference on Jobs and Development, of which I continue to be a co-organizer, brings together researchers and policymakers from around the world each year to share research findings and policy conclusions to address these issues.Har

Turning to the topic of income distribution, there is room here for personal value judgments, which can be laid out and debated. My own judgment is that the most serious economic problem to confront is poverty, conceived of as absolute economic misery – very simply, workers and households being too poor to be able to buy the things deemed necessary for an economically adequate life. Not everyone shares this judgment, preferring to give greater weight to inequality, defined as differences in economic outcomes between some people and others. Early in my career, even before I got to Cornell, the United States Congress called for “New Directions in Development Assistance,” and I was instrumental in getting the Agency for International Development to adopt an anti-poverty focus. As for international organizations, the World Bank used to be an amorphous institution without a clear mission statement. I am told that it was in part because of my efforts that they adopted “A World Free of Poverty” as their defining slogan, and other development banks followed suit.

Tell me about winning the IZA Prize, considered by many to be the equivalent of a Nobel. What is it like to receive such a high-level recognition? How did you react to the news that you had won?

Thank you for bringing that up. The IZA Prize, which I won in 2014, is the top international prize in the field of labor economics. I learned about it by email one evening at home. I turned to my wife, showed her the message on my phone, and said, “OMG. Look at this.” I was stunned. I had had no idea I was in the running.

At the award ceremony, the speaker who gave the laudatory statement was one of my former Cornell Ph.D. students, Ira Gang. Speaking about some of the things he had learned from me back in grad development economics in fall 1979, he said: “[In] influencing thinking, research, policy, [Gary’s] ideas helped form the critical textbooks and discussions about development, to the extent that it becomes the conventional wisdom and not attributable. If these changes seem rather mundane, they aren’t. It is like seeing the film Citizen Kane for the first time: its greatness is missed – it seems like old hat – the failure is in not realizing that this is where the ‘old hat’ was introduced.”

Thank you, Ira.

Would you want to talk about any other awards?

Yes.

I am proud to have been named the inaugural John P. Windmuller Professor of International and Comparative Labor. When I was hired at Cornell, John was the chairperson of the Department of International and Comparative Labor Relations (as it was then known) and the leading internationalist on the ILR faculty. After John’s retirement, I took over as department chair and served in that role for 18 years. You can read more about John’s legacy in R.D. Colle et al., eds., Beyond Borders: Exploring the History of Cornell’s Global Dimensions, Cornell University Press, 2024.

I am proud to be the three-time winner of Cornell’s General Mills Foundation Award for Exemplary Graduate Teaching. Those award plaques are placed prominently in my office, alongside the IZA award plaque.

I am proud of the many favorable reviews of my books, including praise from four Nobel Prize-winning economists – Amartya Sen, Joseph Stiglitz, George Akerlof and Esther Duflo.

And I am proud of the multitude of thank-you messages and expressions of gratitude from students over the years. Seeing the expressions of understanding on their faces in the classroom was my greatest ongoing professional reward, which I know I will miss in retirement.

You are a compassionate teacher eager to help students understand the material. How did your teaching style evolve?

Economics was hard for me and did not come easily. For this reason, I tried always to be patient with students, even on those rare occasions when the student revealed a distinct lack of effort. I remember telling an assistant professor that our job as faculty is to offer excellent learning opportunities to the students who take our courses, and that students are free to seize those learning opportunities or not.

Let me share one insight I had midway through my teaching career. Because there is so much material in the readings, students need to be guided on what are the most important things to learn and what the right answers were to similar questions asked in the past. This led me to print up the previous year’s exam questions along with “A” answers that had been written by students. (Yes, in economics, there often are right answers.)

Teaching the ILR master’s students posed a particular challenge: many master’s students had had little or no economics in their previous coursework. The master’s courses succeeded because I met them at the level they came in at and taught them what they needed to know about principles of economics.

Looking ahead, master’s-level labor econ will be taught by Associate Professor Evan Riehl this coming year. I’m looking forward to sharing my insights and course materials with him as he takes hold of the torch.